North African Moors: Early Transatlantic Voyages and Cultural Exchange

Prologue: Names as Living History

The story of human identity is etched in the names we choose and those imposed upon us. When Jesse Jackson stood before the National Black Media Coalition in 1988 advocating for “African American” as the preferred term, he was participating in a centuries-old tradition of self-definition that connects directly to much older questions about transatlantic contact and cultural exchange. This moment – seemingly about modern identity politics – was in fact the latest chapter in an ancient story of how peoples name themselves and understand their place in the world.

Chapter 1: The Moorish Enigma – Between History and Legend

The medieval Moorish world stretched from the bustling markets of Marrakesh to the luminous libraries of Córdoba, forming a nexus of trade, science, and spirituality that influenced three continents. But while its intellectual and architectural legacies are well-documented, less explored is the possibility that its maritime ambitions extended far beyond the familiar coasts of the Mediterranean. From the docks of North Africa and Iberia, Moorish sailors may have set their sights westward, following winds and currents into the great expanse of the Atlantic—perhaps centuries before Columbus.

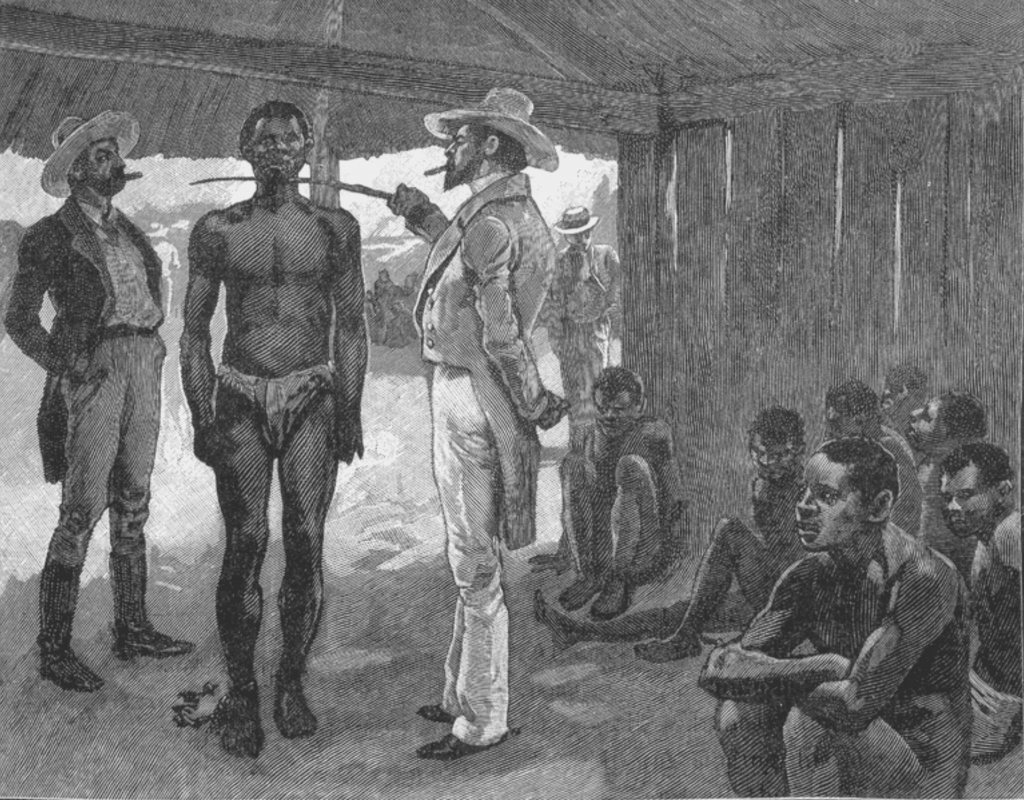

One of the most compelling accounts of such early exploration comes from the Kingdom of Mali, whose wealth and sophistication rivaled any contemporary European monarchy. According to the 14th-century Arab historian Al-Umari, Mansa Musa—Mali’s most famous ruler—recounted during his 1324 pilgrimage to Cairo that he only became king because his predecessor, Mansa Abu Bakr II, relinquished the throne in 1311 to pursue a voyage across the western ocean. Abu Bakr is said to have outfitted a fleet of 400 ships with provisions and men, determined to find the edge of the known world. Only one ship returned, its crew describing a strange phenomenon: a “river in the sea,” likely a poetic reference to the Amazon River plume, where the massive outflow of freshwater from South America visibly discolors and alters the salinity of the Atlantic for hundreds of miles offshore.

Centuries later, another enigmatic clue would surface in the form of the Piri Reis map (1513), one of the most intriguing artifacts of early cartography. Compiled by the Ottoman admiral and scholar Piri Reis, the map portrays the coastlines of South America and parts of Africa with surprising accuracy, despite being drawn only two decades after Columbus’s first voyage. In his marginal notes, Piri Reis stated that he had used “about twenty charts and mappae mundi” to compile his map—some of them dating back to antiquity, including reputedly from the time of Alexander the Great. Scholars such as Gregory McIntosh and Fuat Sezgin suggest that these older sources may have included Moorish or Arabic maritime knowledge, long preserved in the Islamic world through libraries, oral traditions, and navigational treatises. These lost charts, potentially passed down through Andalusian mariners or North African scholars, could have preserved geographic knowledge of lands across the Atlantic well before 1492.

Meanwhile, across the ocean in the tropical lowlands of present-day Veracruz, the colossal stone heads of the Olmec civilization continue to spark debate. Carved between 1200 and 400 BCE, these monumental sculptures—some weighing over 20 tons—bear facial features that have been interpreted by some, notably Guyanese-American historian Ivan Van Sertima, as evidence of African influence. Van Sertima’s controversial 1976 book They Came Before Columbus argues that African voyagers, possibly from West Africa, made contact with Mesoamerican cultures, leaving behind artistic and cultural imprints. He draws comparisons between the Olmec heads and terracotta figures from the Nok civilization of Nigeria, noting similarities in facial structure, proportions, and style.

Mainstream archaeologists have largely rejected these theories, citing a lack of direct archaeological evidence and emphasizing the independent development of Mesoamerican civilizations. However, new developments in genetic research have reopened the conversation. A 2018 study published in Nature identified traces of West African-related DNA in pre-Columbian Indigenous populations of Mexico, raising tantalizing questions about ancient migration and contact. While the study attributed most African genetic presence to post-Columbian events, such as the transatlantic slave trade, a small portion of the data suggested the possibility—however faint—of earlier, undocumented connections.

Together, these fragments—a forgotten voyage from Mali, a mysterious map from Istanbul, monumental heads in Mesoamerica, and cryptic strands of DNA—form a mosaic of possibility. Though far from conclusive, they challenge the Eurocentric narrative of discovery and invite a broader, more inclusive interpretation of global history: one where African and Islamic civilizations were not only observers of the Age of Exploration but possibly early participants, navigating the deep waters of the Atlantic in pursuit of knowledge, trade, and destiny.

Clarifying the Background:

The Moors were a group of Muslim peoples from North Africa, specifically the Maghreb region, which includes modern-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. North Africa is geographically located on the continent of Africa, but the populations there have historically been ethnically diverse, reflecting centuries of migrations, conquests, and cultural exchanges.

North African Ethnic Diversity:

- Berbers (Amazigh):

- The Berber people are indigenous to North Africa, with a presence that predates the Arab expansion in the 7th century. Berbers are genetically diverse, with some individuals having lighter skin tones, while others have darker skin tones.

- The Berber populations include people who could be described as light-skinned, medium-toned, or darker-skinned, and some Berbers are of Black African descent due to centuries of migration, trade, and intermarriage with sub-Saharan Africans.

- Arabs:

- The Arab expansion beginning in the 7th century brought large numbers of Arabians into North Africa, mixing with the Berber populations. Many Arabs were lighter-skinned, though, over time, Arab-Berber mixing occurred.

- Sub-Saharan Africans:

- Over centuries, there was considerable movement between North Africa and the sub-Saharan regions due to the trans-Saharan trade routes, including the slave trade and cultural exchange.

- Thus, by the time the term “Moor” was widely used in the context of the Islamic rule of Spain (Al-Andalus), the population included a mix of lighter-skinned Berbers, Arabs, and Black Africans who had strong cultural and genetic ties to the wider African continent.

What the Term ‘Moor’ Actually Means:

- The term “Moor” was not a racial label in the modern sense. It was used in medieval Europe to describe people of Muslim faith from North Africa.

- When Europeans referred to “Moors”, they were often describing Muslims from Al-Andalus (Spain) or North Africa who were involved in the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula during the 8th to 15th centuries.

- The Moors, by this definition, were culturally and religiously Muslim people, but they included ethnically diverse groups. Some of them were Black, particularly those who came from West Africa or sub-Saharan regions. Others were lighter-skinned, such as Berber and Arab populations.

Historical Context of the Moors:

- The Moors in Spain and Portugal (Al-Andalus) from the 8th century onward included individuals of varied skin tones and ethnicities, reflecting the multicultural nature of the Muslim world.

- Al-Andalus was a place of great cultural exchange where Africans, Arabs, Berbers, Jews, and Christians coexisted and contributed to advances in science, medicine, philosophy, and the arts.

- The Berbers, who are indigenous to North Africa, often had a wide range of physical appearances, from lighter-skinned individuals to darker-skinned ones, with some of them having mixed heritage due to centuries of contact with both Arab and sub-Saharan African populations.

The Question of ‘Blackness’ in the Historical Context:

- In the context of the Moors, it is important to avoid applying modern concepts of race to medieval populations. The way people were classified based on physical appearance during the medieval period didn’t adhere to modern racial categories.

- Black Africans in North Africa and the broader Muslim world were an essential part of society and had significant cultural and religious influence, particularly in West African empires like Mali and Songhai. The idea that only sub-Saharan Africans were “Black” does not reflect the complexity of ethnic and cultural identities in history.

The Moors were not homogenous in terms of appearance or ethnicity. Some Moors were Black Africans, particularly those from West Africa, while others were Berber or Arab, who could have a range of skin tones, including lighter complexions. The North African region, where the Moors originated, has long been a cultural and genetic crossroads, which contributed to the diversity of the people who would become known as “Moors.”

This diversity is crucial to understanding the historical complexities of North African, Moorish, and Iberian interactions, and modern racial categories cannot fully capture the multifaceted identities of these groups during medieval times.

Chapter 2: The Gullah Geechee – Living Bridges Between Worlds

On Sapelo Island, Georgia, the legacy of Bilali Mohammed and his descendants offers an extraordinary glimpse into the intersection of African, Islamic, and American cultural traditions. Bilali Mohammed, a prominent African Muslim who was enslaved and brought to the island in the early 19th century, remains a significant figure in the history of African cultural retention in the Americas. His Arabic manuscript, known as the Bilali Document, is a rare and precious piece of history. This manuscript, a fragile record of Islamic law transcribed from Bilali’s memory, stands as one of the few surviving examples of Arabic literacy among enslaved Africans in the United States.

The Bilali Document and Its Significance:

- The Bilali Document contains teachings from Islamic law and is written in Arabic, a language that was integral to Bilali’s identity and education. This document represents more than just a legal text; it is a profound testament to the ways in which African enslaved people in the Americas were able to preserve their religious and cultural practices despite the brutal systems of enslavement and forced cultural assimilation.

- The preservation of Arabic literacy by Bilali Mohammed and his descendants is an exceptional example of how enslaved Africans brought their knowledge, beliefs, and practices to the Americas, often in disguised forms to avoid detection and punishment. In a society that sought to erase the African identity, the ability to retain Arabic literacy—which for many of Bilali’s descendants was an act of resilience and resistance—speaks to a deeper connection to African heritage and spirituality.

Cultural Conservators: The Gullah People

Bilali Mohammed’s descendants are part of the Gullah-Geechee community, a group of African-descended people living along the coastal Lowcountry of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The Gullah language, a creole language spoken by the Gullah people, is a linguistic time capsule, preserving significant elements of African languages and cultures. This unique language, spoken with a distinctive rhythm and cadence, is a linguistic fusion of African languages, primarily from West and Central Africa, along with English influences, but still retains African roots.

Key Words and Their African Origins:

- Tote (from the Wolof word “tota,” meaning “to carry”): The word “tote” in Gullah closely mirrors its Wolof counterpart, a language spoken by many enslaved people from Senegal and Gambia. The retention of this term reveals a linguistic thread linking the Gullah language to West Africa, where Wolof was widely spoken.

- Goober (from the Kikongo word “nguba,” meaning “peanut”): The word “goober” is an excellent example of how Kikongo, a language spoken by enslaved people from Central Africa, influenced the Gullah language. The peanut, a crop that became important in the South, is tied to Kikongo-speaking communities who cultivated it long before its widespread adoption in the Americas.

- Salamu (from Arabic, meaning “peace”): The Gullah word “salamu” retains the Arabic greeting used by Bilali Mohammed’s descendants, reflecting the Islamic influences that persisted in the community long after the introduction of Christianity. The Arabic word for peace, “salaam,” was not only used by Muslims but also became part of the broader cultural fabric of African-descended communities in the Lowcountry.

Preserving African Cultural Practices:

Beyond language, the Gullah-Geechee community is known for preserving a variety of African cultural practices that were retained across generations. This cultural preservation is not simply a matter of tradition, but an embodiment of the resilience and resourcefulness of African people under the brutal systems of enslavement and colonization.

African Agricultural Techniques:

- The Gullah people are renowned for their ability to preserve and practice traditional African crop cultivation techniques. They maintained methods of farming that were passed down from their African ancestors, including the cultivation of rice, okra, and sweet potatoes, which were essential crops in West African agriculture.

- The knowledge of these crops and farming techniques enabled the Gullah people to build a thriving agricultural community in the southern United States. These practices also made them key contributors to the economic development of the South, especially in the rice plantations of the Lowcountry.

Sweetgrass Basket Weaving:

- One of the most enduring cultural artifacts of the Gullah people is their sweetgrass baskets, which are woven with remarkable skill and precision. The art of basket weaving among the Gullah people is directly linked to African traditions, particularly those from the Senegalese and Guinean regions. These baskets are constructed using the coil weaving technique, which is virtually identical to traditional methods used in West Africa, particularly in the Senegalese region.

- The sweetgrass baskets served a functional purpose for the Gullah people in daily life, but they also became a symbol of cultural continuity, demonstrating how African art forms survived the transatlantic slave trade. Today, the Gullah basket weavers continue to produce these works of art, and their craftsmanship is recognized as a distinctive cultural heritage of the African-American community.

Oral Histories and Spiritual Traditions:

The Gullah people’s oral traditions also preserved stories, beliefs, and spiritual practices that linked them to Africa. These oral histories often center on tales of “Ole Time Africans”—ancestors who arrived on the shores of the Americas before the official start of the transatlantic slave trade. These stories, passed down through generations, embody the Gullah community’s deep connection to African identity and memory.

- Among the stories are accounts of ancestors who could “walk on water”, which may refer to metaphorical memories of skilled sailors who navigated the vast and unpredictable waters of the Atlantic. The stories could also reflect the remarkable maritime traditions of African peoples who were expert navigators and sailors, particularly those from the West African coast, where the maritime skills of the Wolof, Mandinka, and other peoples were highly valued.

Gullah Identity and Moorish Influence:

The Bilali Document serves as an important artifact within the broader context of Islamic and African influence on the Gullah-Geechee culture. The Gullah people have a unique and complex identity that reflects not just the influence of West and Central Africa, but also Islamic and Arab influences introduced by ancestors like Bilali Mohammed.

Some Gullah families, such as those descended from Bilali Mohammed, still maintain links to Islamic traditions, and this connection is seen in their religious practices, use of Arabic words, and even cultural symbols. This preservation of Moorish heritage within the Gullah community highlights the interwoven history of Islamic, African, and American cultures that continues to shape their identity today.

The Gullah-Geechee people of Sapelo Island, Georgia, are unparalleled cultural conservators in the Americas. Through their retention of African language, agricultural techniques, crafts, and oral traditions, they have preserved a vital link to their African roots, bridging the gap between African history and the American experience. The Bilali Document, sweetgrass basket weaving, and linguistic continuity in the Gullah language all stand as testaments to the resilience, ingenuity, and pride of African-descended peoples in the Americas. Their preservation of these traditions enriches our understanding of the transatlantic slave trade, African diaspora, and cultural memory, ensuring that the stories of their African ancestors continue to live on in the hearts and minds of future generations.

Chapter 3: The Pigmentation Puzzle – Science Meets Storytelling

Human pigmentation is a subject that combines genetics, history, and cultural storytelling, weaving a complex narrative that reveals not only the biological adaptations of diverse populations but also the perceptions, beliefs, and practices of the peoples who lived in those regions. In this chapter, we will explore the frozen mummies of ancient South America, the striking visual depictions of different ethnicities in Maya art, and the deep genetic insights into skin pigmentation that scientists are uncovering through modern DNA analysis.

Juanita: The Andean Mummy and the Genetic Legacy of the Andes

In 1995, the discovery of a frozen mummy on the slopes of Mount Ampato in Peru sent shockwaves through the world of archaeology and genetics. Known as Juanita, she was a young Inca girl who had been sacrificed as part of an Inca religious ritual, her body preserved by the cold and dry conditions of the high Andes for over 500 years. The preservation of her light brown skin is a powerful reminder of the ways in which human bodies and cultures adapt to their environment, even in the most extreme conditions.

Juanita’s skin color is one of the most striking features of her remains, and the revelation of her SLC24A5 gene variants tells a story of Andean adaptation. The SLC24A5 gene is known to play a key role in the production of melanin, the pigment responsible for skin color. Modern genetic studies have shown that this gene variant is common among people of European descent, but it is also present in indigenous populations of the Andes, suggesting an adaptation to the region’s high-altitude sunlight. Unlike other populations that developed darker skin as protection against the intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation of the tropics, the indigenous people of the Andes adapted in a different way, likely due to the region’s more moderate UV levels at high altitudes.

The presence of these lighter skin gene variants in Juanita gives us valuable insight into the genetic makeup of pre-Columbian Andean peoples. It also challenges the simplistic narrative that darker skin is solely a product of equatorial environments. The genetic variation found in Juanita suggests that Andean peoples were not only resilient in the face of extreme environments but also that their skin pigmentation was the result of millennia of evolutionary adaptation, balancing the need for UV protection with other environmental factors like cold temperatures and the availability of sunlight at higher altitudes.

The Chinchorro Mummies: Dark and Ancient

While Juanita’s light brown skin offers insight into the evolution of pigmentation in the Andes, the Chinchorro mummies of northern Chile present an entirely different aspect of skin color and human adaptation. These mummies, which date back over 7,000 years, are some of the oldest artificially preserved human remains in the world. Unlike Juanita, the Chinchorro mummies exhibit dark, leathery skin, a stark contrast that raises important questions about the origins and adaptation of this ancient population.

The Chinchorro people, known for their maritime culture, thrived along the coastline of the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth. The mummies show the advanced preservation techniques used by the Chinchorro, who practiced artificial mummification long before the Egyptians. However, it is not just their method of preservation that captivates scientists and historians; it is their dark pigmentation. Despite the arid and sun-scorched environment of the Atacama, the Chinchorro mummies did not exhibit the expected lighter skin tones commonly seen in other ancient South American populations.

Modern geneticists have connected the Chinchorro people to the ancient Pacific populations, suggesting that their dark skin may not have been a result of African ancestry but rather a phenotype that developed through adaptation to the sun’s rays over thousands of years. The darker pigmentation of the Chinchorro people could have been an evolutionary response to the intense UV radiation of the Pacific coastline, a factor that may have led to a higher melanin production, providing protection from sunburn and skin damage in a region where sunlight was extremely harsh, even in the desert.

This genetic analysis challenges the once-held notion that dark skin was only a trait found in sub-Saharan Africa, showing instead that dark pigmentation was an adaptation that could occur in populations living in various parts of the world with high UV exposure, including the Pacific coast of South America.

The Maya and the Artistic Representation of Skin Color

In the ancient Maya city of Bonampak, located in what is now modern-day Mexico, a set of murals dating back to around 800 CE provides a fascinating glimpse into how the Maya viewed ethnic diversity and skin color. The murals depict various scenes of courtly life, including the rituals of royal sacrifice and ceremonial dance. The most striking aspect of these murals is how the Maya artists chose to represent their captives and royalty.

The captives—often depicted in dramatic scenes of torture and execution—are shown with deep black skin tones, while royalty and noble figures are portrayed with lighter skin tones, often painted in bright reds or ochres. This artistic distinction raises intriguing questions: Were these depictions simply a reflection of artistic convention, or did they offer an ethnographic record of how the Maya perceived different peoples?

Modern scholars have debated whether these murals were symbolic representations of status and power or whether they were an accurate reflection of the ethnic groups that the Maya interacted with. The dark skin of the captives could represent the outsiders or foreigners who were captured in warfare, while the lighter-skinned figures of royalty may have been an attempt to denote higher social status or noble lineage.

While we may never know the exact motivations behind these artistic choices, modern DNA research offers some intriguing possibilities. The Yanomami people of the Amazon rainforest, for example, possess unique MFSD12 gene variants, which are linked to exceptionally dark skin. These genetic traits are thought to have developed over thousands of years in response to the equatorial sun and the high UV radiation in the Amazon. The Maya may have had contact with or knowledge of these populations, as their depictions of dark skin could reflect an awareness of the skin pigmentation of different groups living in the broader region of Central America and the Amazon.

The portrayal of skin color in Bonampak’s murals suggests that the Maya not only had complex and nuanced views on ethnicity and social hierarchy but also that they understood the relationship between geography, sun exposure, and skin pigmentation.

Modern Insights into Amazonian Skin Pigmentation

To understand the genetic roots of the Maya’s depictions of dark skin, we look at the Yanomami, one of the most genetically distinct populations in South America. The MFSD12 gene found in the Yanomami and other Amazonian tribes is responsible for the exceptionally dark skin pigmentation seen in these populations. MFSD12 is a gene variant that is linked to the production of melanin, and its presence in the Yanomami helps them adapt to the high UV conditions of the Amazon.

This genetic marker is crucial in the understanding of how populations living in areas with intense sunlight, like the Amazon rainforest, evolved to produce darker skin as an adaptation to protect against sun damage. The Yanomami’s dark pigmentation is likely a result of selective pressure over millennia, as they adapted to one of the most biologically diverse and sun-drenched environments on Earth.

As modern DNA analysis continues to refine our understanding of human evolution and the role of genetics in shaping physical traits like skin color, the story of human pigmentation becomes a fascinating tale of migration, adaptation, and survival. From the light brown skin of Juanita to the dark leathery skin of the Chinchorro and the Maya depictions of skin color, the historical and genetic evidence underscores the complexity of how humans interact with their environment and how those interactions are reflected in both their physical traits and their cultural expressions.

The pigmentation puzzle is a multifaceted and deeply complex story. By combining genetic data, archaeological evidence, and cultural observations, we can begin to piece together a richer, more detailed understanding of human history. From the high-altitude adaptation of the Andean people to the dark skin of the Chinchorro mummies and the artistic representations of skin color in the Maya murals, these stories of pigmentation show that human beings have always adapted to their environments in ways that are both biologically and culturally significant. The genetic traces of these adaptations offer an intriguing look into the past, offering clues about ancient peoples, their migrations, and their ongoing legacy in the world today.

Chapter 4: The Forgotten Nations – Indigenous Black America Before Columbus

Opening Narrative: The Bones That Rewrite History

In the humid depths of Lapa Vermelha, Brazil, in 1975, archaeologists unearthed a skull that would shake the foundations of American history. Luzia, as she came to be known, was no ordinary ancient skeleton. Dating back 11,500 years, her cranial structure bore unmistakable Australo-Melanesian features—a broad nasal cavity, pronounced prognathism, and other traits more commonly associated with Indigenous Australians and Africans than with later Native American populations.

Meanwhile, across the continent in Mexico’s Gulf Coast, the Olmec colossal heads—17 monumental stone sculptures weighing up to 40 tons each—stared silently across the centuries. Their flattened noses, full lips, and braided helmets bore an uncanny resemblance to the Mande warriors and Nok artisans of West Africa.

These were not isolated anomalies.

From the dark-skinned Yuchi elders of Tennessee to the black Carib warriors of the Lesser Antilles, the Americas were never the racially monolithic “New World” that European colonizers later claimed. Long before the first slave ships breached the horizon, Black civilizations thrived here—some indigenous to the land, others arriving through forgotten voyages, all systematically erased from our history books.

Section 1: The First Black Americans – Evidence of Pre-Columbian Presence

A. The Olmec Enigma: Africa’s Stone Faces in Mesoamerica (1200–400 BCE)

The Olmec civilization, considered the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica, left behind one of archaeology’s most tantalizing mysteries. At sites like La Venta and San Lorenzo, massive stone heads—some standing over 9 feet tall—depict unambiguously African facial features:

- Broad, flattened noses with wide nostrils

- Full, everted lips characteristic of West African populations

- Helmets adorned with braided patterns identical to Mande warrior regalia

The Van Sertima Controversy

In his groundbreaking 1976 work They Came Before Columbus, Guyanese historian Ivan Van Sertima presented compelling evidence for pre-Columbian African contact:

- Malian Voyages: Historical accounts suggest Emperor Abubakari II dispatched 2,000 ships westward in 1311. While most dismiss this as legend, identical gold weights used by the Akan of Ghana and the Maya suggest cultural exchange.

- Botanical Evidence: African crops like bottle gourds and cotton appear in American archaeological sites centuries before Columbus.

- Linguistic Echoes: The Olmec word for “sun” (yop) bears striking resemblance to the Egyptian Aten and Mande ya.

“The academic establishment didn’t just reject Van Sertima’s work—they ridiculed it,” notes anthropologist Dr. Clyde Winters. “But when you compare a Benin bronze to an Olmec sculpture, the artistic continuity is undeniable.”

B. The Black Pacific Hypothesis: Luzia and Beyond

Luzia’s discovery shattered the Clovis First model of American settlement. Anthropologist Walter Neves’ 1999 analysis confirmed her skull showed:

- Strong Australo-Melanesian affinity (shared with Indigenous Australians and Melanesians)

- No relation to later Native American populations

This suggests multiple migration waves, including:

- The Coastal Route: Seafaring groups from Sundaland (modern Indonesia) may have reached South America 15,000 years ago.

- Atlantic Crossings: The Canary Current creates a natural conveyor belt from West Africa to Brazil—a route possibly used by ancient mariners.

The Chinchorro Mummies (Chile, 5000 BCE)

These dark-skinned, woolly-haired mummies—the oldest in the world—show no genetic link to modern Native Americans, further complicating the peopling narrative.

C. Oral Histories: When the Land Remembers What the Books Forgot

Native traditions across the Americas whisper of Black predecessors:

- Cherokee “Moon-Eyed People”: Described as nocturnal, dark-skinned mound builders who fled underground.

- Washitaw Oral Records: Claim descent from the Ancient Ones who settled the Mississippi Valley millennia ago.

- Hopi Legends: Speak of Kasskara, a sunken Black civilization that preceded their own.

Section 2: The Red/Black Fallacy – How Europe Distorted American Identity

The persistent image of Native Americans as uniformly “red-skinned” stands as one of history’s most consequential racial distortions. Early European explorers recorded a far more complex reality—Columbus’s initial 1492 account described the Taíno as “neither black nor white,” comparing their complexion to olive-skinned Canary Islanders, while Spanish chroniclers like Oviedo noted Caribbean tribes with skin “black as those from Guinea.” These unfiltered observations reveal a spectrum of Indigenous complexions ranging from light bronze to deep brown and ebony across different regions, documenting phenotypic diversity that later European narratives would systematically erase.

The homogenization of Native peoples into the “Red Indian” stereotype emerged through multiple intersecting factors. Many nations like the Cherokee Ani-Wodi (Red Paint Clan) used red ochre ceremonially, leading Europeans to associate the color with all Indigenous peoples. Linguistic mistranslations compounded this when Algonquian terms using “red” metaphorically for “living” or “sacred” were interpreted literally. By the 18th century, pseudoscientific racial taxonomies like Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1758) codified this simplification, dividing humanity into four crude chromatic types—white Europeans, black Africans, yellow Asians, and red Americans. This artificial framework served colonial aims by transforming a mosaic of human variation into rigid racial boxes, enabling the political treatment of diverse nations as a monolithic group for land dispossession and cultural erasure.

Numerous Indigenous communities defied this imposed “red” classification throughout the colonial period. English traders described the Yuchi and Yamasee as “swarthy as mulattoes” with African-textured hair, while Spanish missionaries documented California’s Esselen people with exceptionally dark skin and filed teeth—physical traits suggesting ancient Pacific connections. The Black Caribs (Garifuna) of St. Vincent exhibited such pronounced African features that British colonists initially mistook them for escaped slaves rather than recognizing their deep Indigenous roots. These accounts collectively attest to pre-colonial America’s rich phenotypic tapestry, one that European racial frameworks deliberately obscured.

The consequences of this taxonomic violence endure today. The “Red Indian” stereotype has marginalized Afro-Indigenous identities from the Black Seminoles to Louisiana’s Washitaw Nation, while tri-racial groups like the Melungeons were forced into artificial racial categories denying their complex heritage. Modern genetic research now validates what early European accounts first documented: West African haplogroups in some Native lineages predate the transatlantic slave trade, and Olmec colossal heads bear undeniable African morphological features. Contemporary battles for recognition—from Seminole Freedmen’s citizenship claims to Washitaw land rights struggles—stem directly from this centuries-long flattening of Indigenous diversity.

As we re-examine these historical records, a profound truth emerges: the Americas were never monochromatically red, but rather a living canvas of human variation that colonial systems of categorization sought to simplify and control. This reckoning demands more than academic correction—it requires us to confront how these fabricated racial constructs continue to shape Indigenous identities, rights, and representation in the modern world. The recovery of these erased histories offers not just a truer past, but pathways toward more just futures.

Contrary to the later “Red Indian” stereotype, initial European accounts described Native populations with astonishing diversity:

| Group | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Taino | “The color of Canary Islanders” (bronze) | Columbus, 1492 |

| Carib | “Black as Guineans” | Peter Martyr, 1516 |

| Aztec | “Brown like chestnuts” | Bernal Díaz, 1521 |

| Yamasee | “Jet-black with filed teeth” | English settlers, 1702 |

The “red” classification emerged from:

- Ochre Use: Many tribes used red paint ceremonially (e.g., Cherokee Ani-Wodi).

- Linguistic Mistranslation: Some Algonquian languages used “red” metaphorically for “living.”

B. The Melungeon Conspiracy: Hiding Tri-Racial America

In the Appalachian foothills, the Melungeons—a mixed population of Black, Native, and European ancestry—were systematically reclassified through:

- “Portuguese” Myth: Families claimed Mediterranean ancestry to avoid Jim Crow laws.

- “Black Dutch” Fiction: A euphemism for mixed-race individuals in census records.

Genetic Truth: 2012 DNA studies confirmed Senegalese and Native American markers in Melungeon lineages.

Section 3: The Living Legacy – Black Native Nations Today

A. The Washitaw Nation: Louisiana’s Hidden Empire

- Recognition: Officially acknowledged by the UN in 1991 as indigenous autochthons.

- Land Claims: Hold original Spanish land grants to over 1 million acres in the Mississippi Delta.

B. The Yuchi Language Isolate

Their unrelated tongue (no links to Algonquian, Iroquoian, or Muskogean families) suggests:

- Pre-Cherokee presence in the Southeast

- Possible linguistic ties to West Africa (ongoing research)

C. Seminole Freedmen Struggle

Despite 1866 treaties guaranteeing citizenship, Black Seminoles still fight for tribal rights against modern exclusionary policies.

As DNA analysis grows more sophisticated, every new genome sequenced threatens to rewrite our origin stories. From the African-like Olmecs to the Melanesian-featured Pericú of Baja, the evidence mounts:

America was always multicultural. America was always Black.

The question is no longer if Black civilizations existed here before Columbus, but how many, how influential, and why we’ve been taught to forget them.

Reclaiming Native America’s True Colors: The Diverse Skin Tones and Cultures Erased by Colonial Myths

The Americas before colonization were a living tapestry of human diversity—a spectrum of skin tones ranging from golden-copper to deep ebony, with cultural traditions as varied as the landscapes they inhabited. European accounts from first contact reveal what modern stereotypes have long obscured:

The True Mosaic of Native Complexions

- Caribbean Taino: Ranging from “honey-gold” (Columbus) to “dark as mahogany” (Oviedo), with straight to wavy hair textures

- Amazonian Tribes: Documented by Spanish explorers as having “cinnamon-bronze skin with reddish undertones”

- Mississippian Mound Builders: Described by French traders as “copper-skinned with tattooed sun patterns”

- Pacific Northwest Nations: Noted for their “light olive complexions” by Russian explorers, adapted to cloudy coastal climates

- Southwestern Pueblos: Recorded as having “sun-browned terra cotta skin” by Coronado’s expedition

The Lost Cultures of Pigmentation

Many tribes had sophisticated traditions around skin tone:

- Choctaw “Hattak Holba”: A social class system recognizing different skin tones’ ceremonial roles

- Navajo “Nizhóní”: The cultural ideal of “harmonious coloration” between skin, hair, and environment

- Iroquois berry dyes: Used to temporarily darken skin for spiritual ceremonies

The Science Behind the Diversity

Anthropologists now recognize three key factors creating this variation:

- Ancient Migration Waves: Different founding populations entering the Americas at separate times

- Local Adaptations: Evolutionary responses to UV exposure, altitude, and climate

- Cultural Practices: Differential sun exposure based on gender roles and occupations

The Living Legacy

Modern DNA studies confirm:

- 23 distinct genetic clusters existed pre-contact

- Some Amazonian groups show Australo-Melanesian markers

- California’s Chumash retain unique genetic variants for melanin production

This rich human diversity was systematically erased by colonial racial categories that served to:

- Simplify complex societies for control

- Justify land dispossession

- Create artificial racial hierarchies

The truth resurfacing today shows Native America was never a monochrome “red” continent, but a vibrant civilization that celebrated its full spectrum of human variation—knowledge that is now helping Indigenous communities reclaim their complete heritage beyond colonial stereotypes.

No Comments